The C&O Canal National Historical Park in Maryland is one of the longest and narrowest national parklands in the country. The main walking and cycling route along its entire length is the canal towpath, all 184.5 miles of it. But near the Great Falls of the Potomac River, the park broadens out to include the surrounding hills and river islands. This area has an extensive network of trails that makes it one of the best places to hike near Washington, D.C.

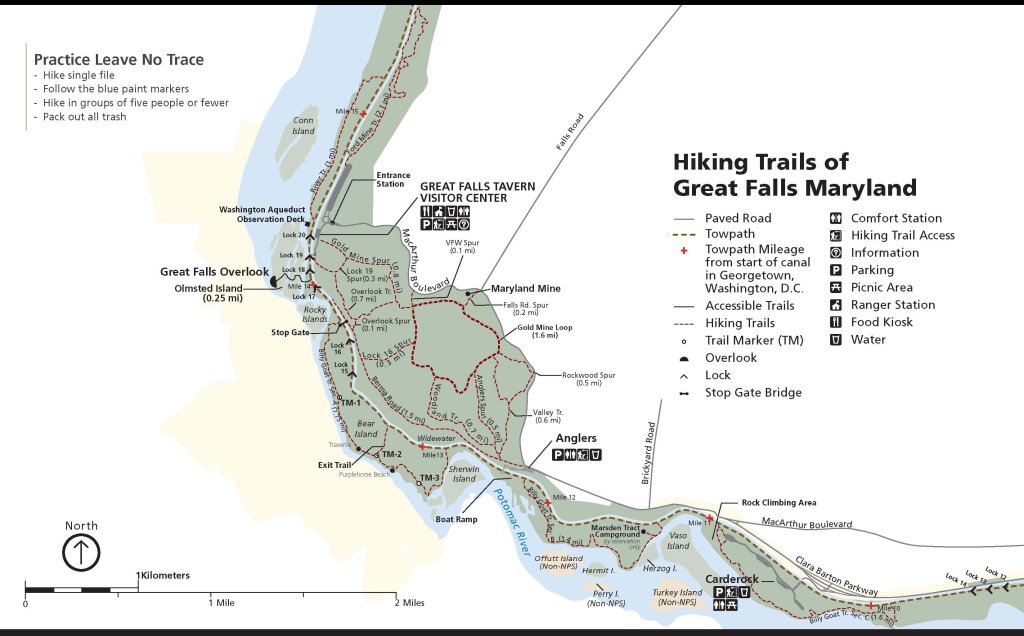

The Park Service has a very good trail map (shown below). The reverse side has trail lengths, levels of difficulty, and other basic information. I recommend picking one up at the park visitor center in Great Falls Tavern. If the building is closed, there should be a box outside the front door with maps. You can also download a PDF version; I’ve provided links at the end of this post.

This Trail Guide

My guide to the trails here is intended to complement the Park Service map by providing further information and suggestions based on my own experience walking the trails. I won’t go into a lot of detail about what you’ll see along the way. That’s for you to discover.

The trails can be divided into three basic groups: the trails near the river or canal in the northernmost part of the park, the trails in and around the Gold Mine Loop area in the central section of the park, and the Billy Goat Trail system, which extends for several miles along the river downstream from Great Falls.

The Northern Trails

Great Falls Overlook Trail

0.25 Miles – Easy

The park trail map description refers to this as the Olmstead Island Bridges, perhaps to avoid confusion with the Overlook Trail in the Gold Mine Loop area. It is the easiest and one of the shortest trails in the park, and one you shouldn’t miss. It consists of a series of boardwalks and bridges that lead from the canal towpath across Olmstead Island to the Great Falls Overlook. Here you will find the best view of the falls in the park.

The trail starts about a quarter mile down the towpath from Great Falls Tavern, so it’s about a 1-mile round trip to the overlook and back. I advise people who don’t want to go even that far to at least go out onto the short bridge right at the trailhead that crosses over an impressive torrent.

The Great Falls Overlook Trail is wheelchair accessible. No dogs or bicycles are allowed. You can lock your bike to a bike rack at the trailhead.

River Trail

1 Mile – Easy

If a flat walk through the woods beside a river sounds appealing, the River Trail is for you. A short walk from Great Falls Tavern, the trail enters the woods from the towpath just beyond the broad observation platform overlooking the river. It emerges back onto the towpath about a mile away, making for an easy 2-mile round trip, half on trail and half on towpath. Be aware that the low-lying trail can get mucky or impassable after a heavy rain or a flood.

The river here is as flat and placid as the trail. It backs up behind a low dam built to funnel water into the Washington Aqueduct intake beneath the observation platform. I’m told you can spot from the trail a couple of bald eagle nests in trees across the river. The upper end of the trail takes you past some of the widest sycamore tree trunks I have ever seen.

Ford Mine Trail

2.1 Miles (round trip) – Moderate

Traversing an area once mined for gold, the Ford Mine Trail begins and ends at the far lower corner of the parking lot and makes a long loop through the woods paralleling the canal. Whenever I infrequently walk this trail, I wonder why I don’t do it more often. It seems to be one of the park’s least visited trails, so it’s good for getting away from the crowd. And it’s a rather nice walk.

The first third of the trail is mostly wide and level. Where the trail splits into a loop, the trail to the right climbs up and down some low hills and crosses several small streams, providing a bit of exercise. Once you reach the far end of the loop and turn back, the trail becomes less hilly and stays within sight of the canal for much of the way. At an easy pace, I walked the entire trail in about an hour.

The Gold Mine Loop Trails

The Gold Mine Loop area is bordered on one side by MacArthur Boulevard and on the other by Berma Road, a closed road built over the Washington Aqueduct conduit and now used as a trail. This largest wooded section of the park was once the site of Civil War earthworks and later of gold mines, which operated from the 1880s to the 1940s. There are few obvious remains of either, other than terrain that looks unnaturally disturbed. This is one of my favorite places to take a quiet walk in the woods.

Berma Road

1.5 Miles – Easy

Berma Road is a wide and flat trail that runs along the hillside on the “berm” side of the canal (opposite from the towpath) and offers nice views of the former river channel now known as Widewater. The road surface varies from fine gravel to stony to crumbling asphalt but is mostly smooth, with just a few short bumpy stretches if you’re on a bike.

The south end begins at the park parking lot (restrooms here) opposite Old Anglers Inn on MacArthur Boulevard. The north end of Berma Road can be accessed via the stop gate bridge that crosses the canal a half mile from Great Falls Tavern. Berma Road continues a short way past the stop gate bridge. Where it dead-ends, there are nice views of the towpath below and the Potomac River gorge beyond.

If you park at Anglers (as it’s called on the park map), you can make a flat and easy 3-mile loop around the scenic Widewater area via Berma Road and the canal towpath. Starting at the other end at Great Falls Tavern adds another mile. This loop is one of my favorite walks in the park. Spur trails connect Berma Road with the adjacent Gold Mine Loop, creating even more loop hike variations.

Gold Mine Loop

1.6 Miles – Easy

The Gold Mine Loop is the heart of the trail system here. It makes for a pleasant, easy walk through open woodlands with lots of options for longer hikes. The trail is wide and mostly hardpacked dirt, with one stream crossing where you have to step from rock to rock.

All the trails that lead to or branch off from it are rated either easy or moderate, perhaps based on elevation change—you have to go uphill from Berma Road or the Great Falls Tavern area to reach the Gold Mine Loop. You need to watch your footing at few of the steeper and rockier spots on the spur trails, but they aren’t unusually challenging.

Side Trails to Anglers

If you start at Anglers and walk down Berma Road for a short distance, you’ll come to a fenced area containing equipment for the aqueduct. Three trails fan out from here and head uphill to the Gold Mine Loop: the Valley Trail (0.6 mi.), Anglers Spur (0.5 mi.), and Woodland Trail (0.7 mi.). I like to take the Valley Trail, which follows a small stream, and return via the Woodland Trail, which passes by those barely discernible Civil War earthworks.

Side Trails to MacArthur Boulevard

Several short trails branch off the eastern side of the loop and lead to MacArthur Boulevard: the Rockwood Spur (0.5 mi.), Falls Road Spur (0.2 mi.), and VFW Spur (0.1 mi.). These are mainly useful for accessing the loop from surrounding neighborhoods or the VFW Post.

Side Trails to Berma Road or the Canal

These trails are good for creating longer loops. I’ve hiked from Anglers to Great Falls Tavern via one route and returned via a completely different route many times. There are any number of variations you can take. A couple of spots can be a little confusing, especially where other unmarked paths intersect, so watch for trail signs and blazes and bring a map. You can’t really get lost, but you can end up on a different trail than you expected.

The Lock 16 Spur (0.3 mi.) leads directly from the Gold Mine Loop down to Berma Road.

The Gold Mine Spur (0.8 mi.) heads north and then west from the Gold Mine Loop to Great Falls Tavern. Several other trails connect with the Gold Mine Spur.

The Overlook Trail (0.7 mi.) heads west from the Gold Mine Spur and then turns north, passing a couple of nice overlooks of the Potomac River gorge. The short Overlook Spur (0.1 mi.) connects the Overlook Trail to Burma Road.

The Lock 19 Spur (0.3 mi.) starts at Lock 19, not far from Great Falls Tavern, and connects with both the Overlook Trail and the Gold Mine Spur.

There’s an interesting “hidden feature” along the Gold Mine Spur not labeled on the trail map. Walking from the Gold Mine Loop toward Great Falls Tavern, the spur trail takes a sharp left where an unmarked trail intersects from the right. From here the trail runs straight between two high embankments. Where those embankments recede, the trail continues onto a raised bed, which, you may notice, curves around through the woods back to itself in a teardrop shape. What you are walking on is the turnaround for a trolley that once connected Great Falls to nearby Bethesda in the early 20th century. The trolley tracks are gone, but this stretch of the Gold Mine Spur follows the old trolley route through the woods.

The Billy Goat Trail

The Billy Goat Trail consists of three unconnected linear trails—A, B, and C—that in total extend almost 5 miles along the Potomac River downstream from Great Falls. All are reached via the canal towpath. The Billy Goat Trail offers some of the most scenic hiking in the park.

Billy Goat C Trail

1.6 Miles – Easy

Access

Billy Goat C runs through the Carderock area south of Great Falls. Access to parking is via Clara Barton Parkway. To start at the upstream trailhead, park at the northernmost parking lot (restrooms here). The trailhead is a just up the towpath before you reach Mile 11. A short trail from the parking lot to the Carderock cliffs, popular for rock climbing, also leads to the Billy Goat Trail.

The downstream trailhead is at a kink in the towpath just below Mile 10. You can also reach the lower third of the trail from the parking lot near the picnic pavilion.

Hiking the Trail

When I last hiked Billy Goat C, I started at the upstream trailhead. A few yards into the woods at a wooden platform, the trail split. I didn’t see any blazes or signs, so I continued straight instead of turning left. This turned out to be the wrong way but a worthwhile detour. It takes you down to the river along the base of the cliffs, where you’ll often see climbers scaling the rock faces. The trail dead-ends where cliff and river meet.

Except for that initial point of uncertainty, the trail is easy to follow. It starts atop the cliffs and then descends toward river level where the cliffs recede. There are a few rocky spots, including one stream crossing where you need to mind your footing. But otherwise, it’s a pleasant, mostly packed-earth path through the woods. You can walk down to the river in some places. I saw groups of people walking around on the rock outcroppings close to shore.

Near the downstream end, the trail splits again, but here a trail marker points to the correct way—left toward the trailhead, a short distance uphill. I decided to follow the unmarked trail that keeps going straight to see where it went. It continued along the river before angling back up to the towpath at a culvert, about 4/10ths of a mile downstream from the Billy Goat trailhead. There’s nothing special about the unmarked trail to recommend it.

Billy Goat B Trail – Closed

1.4 Miles – Moderate

I hiked Billy Goat B in 2016. Since then, the Park Service closed the trail because of damage from floods and erosion. They are still determining how best to repair or reroute the trail through this ecologically sensitive area. Don’t expect it to reopen anytime soon.

Some people ignore the signs and hike the trail anyhow. I cannot endorse this. I don’t recall anything unique about this trail. It seemed much like Billy Goat C, except with a couple more rocky places to cross. There are lots of other good trails in the park. My advice: respect the Park Service directive and stay off.

Billy Goat A Trail

1.75 Miles – Strenuous

Billy Goat A is the only trail in the park rated as strenuous, and yet it’s also one of the most popular trails. It follows the rim of Mather Gorge and offers splendid views, before dipping down to a couple of small beaches on the river and traversing some low wetlands.

The trail attracts everyone from seasoned hikers to casual walkers woefully unprepared for it. If you want to hike the trail on a weekend or holiday in peak season, go early. It can get crowded. No pets are allowed, and bringing small children is discouraged.

Access

Billy Goat A begins about a half mile down the towpath from Great Falls Tavern, just before you reach the stop gate bridge over the canal. It emerges back onto the towpath at the lower end of Widewater, just below Mile 13. There is only one other access point, the Exit Trail at about the midway point.

During the pandemic, the Park Service made Billy Goat A one way, and it remains so. However, the Exit Trail is a two-way trail, which allows you to exit or enter Billy Goat A at roughly its midpoint and thereby hike just the upper or lower half.

The lower sections of the trail can flood, so when the river rises to a certain level, the Park Service closes Billy Goat A until the waters recede. If it has rained heavily recently, check online or call first to make sure the trail is open.

Safety and Preparedness

Billy Goat A is not unusually long or steep or technically challenging. But much of the trail involves going across or up, over, and down innumerable bedrock outcroppings and boulders. These rocky areas offer endless opportunities to take a wrong step or to slip and fall. Sand deposited by high waters makes some of the rocks close to the river slippery. The trail has some easy stretches that provide a welcome break, but many more where you have to watch almost every step you take. That can get tiring, which further increases your chances of a misstep.

Too many people underestimate how taxing this trail can be after a while, especially if they hike it unprepared, without proper footwear, or without enough water, especially on a blisteringly hot summer day. Too many people hobble out hurt or dehydrated. Others must be rescued.

Well-trained park volunteers called Billy Goat Trail stewards monitor the trail and offer assistance. They are a welcome and comforting presence. Don’t count on one to be around if you need help, but be grateful if there is.

So be prepared and be careful. Read and follow the trail safety recommendations listed on the park map.

Trail Blazes

Keep looking ahead for those blue trail blazes painted on trees and rocks that mark the best route. You can’t really get lost here, but you can make the hike harder for yourself if you stray from the marked trail. Bear Island, which the trail traverses, is a biologically important and sensitive area, so it’s important to stick to the trail for that reason too and not go bushwacking.

When I hiked the trail, I did manage to get off track slightly a couple of times because I couldn’t spot the next blaze. In one spot, I followed what I thought was the trail through tall grasses. “This can’t be right,” I thought, and it wasn’t. I soon found myself back on rock, spotted a blaze, and got back on track. But when I reached the river again, it was unexpectedly on my left. It took me a disoriented moment to realize that the river wasn’t going the wrong way, I was.

Mile Markers

Once you’re on the trail, it’s hard to tell exactly where you are or how far you’ve gone. The Park Service has installed three trail markers (shown on the map) to help you out.

TM-1 is about a third of the way from the trailhead. Up to this point, the going is fairly easy. But there’s a sign here warning of more strenuous hiking ahead. If you have any doubts about whether you want to continue, this is a good place to buck the one-way traffic and turn back.

TM-2 is a short distance past the Traverse, the one cliff you must ascend on the trail. It marks the trail’s approximate midpoint and is where the Exit Trail intersects, the only way off the trail until its downstream end.

TM-3 is just past a narrow wooden bridge (EZ Bridge on Google Maps) over a stream. This marks the approximate two-thirds point of the trail. Not far now.

The Traverse

Before you reach TM-2, you must scale the Traverse, a sloping climb up a 50-foot rock wall. Don’t let the photo of it in the visitor center scare you. It’s a mildly technical climb—you have to use your hands as well as your feet. But I didn’t find it overly difficult. It even seemed a little fun after hiking up and down so many boulders and outcrops.

Right near the top was one spot where I had to pause a moment to figure out where to put my foot next. The trail steward waiting at the top suggested I go to the right. I handed him my hiking pole, and a couple of carefully placed steps later, I hoisted myself up to the top. Not bad! Of course, I was wearing good hiking boots, there was not a line of hikers waiting behind me, and it wasn’t 90 degrees in the shade.

My Hike on Billy Goat A

Billy Goat A had long been the only trail in the park I’d never hiked. I finally decided to tackle it in early June 2023 under ideal conditions—on a lovely weekday morning with mild temperatures and low humidity. I had the trail almost to myself. I encountered only nine people: one guy, a pair of women, a mixed group of five, and a Billy Goat trail steward.

I came prepared. I wore my ankle-high hiking boots and a hat. I put on sunscreen. My waist pack carried two water bottles, a couple of snack bars, a small first aid kit, an ace bandage, and even a whistle. I’m not a kid anymore; I wasn’t taking any chances. I used one of my hiking poles, as I often do on a trail. It helped steady me in some places, but in others it just got in the way. In a few spots, I tossed it ahead of me and used my hands for support instead, which felt easier and safer.

I took my time. Everyone I met on the trail passed me by, except the one guy heading back in the opposite direction. I didn’t find the trail overly strenuous, but the repetitive clambering over rocks did get a little wearying after a while. My foot slipped only a couple of times, both toward the end of the hike on easier parts of the trail, perhaps because I was starting to get careless or tired.

I left Great Falls Tavern for Billy Goat A at 9:00 a.m. I stopped often to take pictures and chatted with the trail steward for a while. I was back at the tavern by 11:40. I estimate that I walked a little less than 4 miles—about 1.75 miles or so on the trail and the rest on the towpath.

I was satisfied that I’d finally done Billy Goat A. But on the other hand, I didn’t feel that it was a trail I’d be eager to hike again anytime soon. An easier walk in the woods where I don’t have to watch my every step seems more to my liking these days.

But who knows?

David Romanowski, 2023

Park Websites

C&O Canal National Historical Park

Billy Goat Trail Information

Trail Map and Guide PDFs

Great Falls Trail Map

Great Falls Trail Descriptions

Related Posts

Gold Mines at Great Falls in Maryland

Walking the Gold Mine Loop