The National Road is not as renowned as Route 66, or the Pacific Coast Highway, or even the Lincoln Highway of early 20th century fame. Although once immensely important, it is now really less of a road than a route, and less of a route than a historical memory of a route.

You can think of the National Road as the first interstate highway, minus all the lanes and the sprawling rest areas. (But with tolls!) Envisioned by George Washington and championed by Thomas Jefferson, it was the first major road financed and built by the federal government.

Initially called the Cumberland Road, it was constructed in the early 1800s to link the Potomac River at Cumberland in western Maryland, with the Ohio River at Wheeling, in what would later become West Virginia. Privately built turnpikes and toll roads extended the route east to Baltimore, at the time the nation’s third largest city and a major port. Thus, the National Road became the first, and for a long time the only, highway connecting the eastern seaboard with the western frontier across the Appalachian Mountains.

The National Road was later improved, surfaced with macadam, and extended farther west across Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. It was most heavily traveled through the mid-1800s, until railroads largely superseded it. It enjoyed a resurgence in the early 1900s with the rise of automobile travel.

On the Road

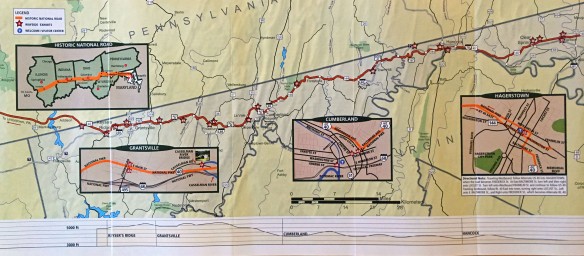

On my way home from a recent trip to Morgantown, West Virginia, I decided to follow the route of the National Road from where it enters western Maryland near Keysers Ridge to Hancock, about 70 miles away. I had driven the route east of Hancock many times, so at that point I’d return to the interstate highway.

So with my “Historic National Road” brochure (from a Maryland visitor center) on the seat beside me, my AAA map of Maryland at the ready, and Google Maps as a backup, I exited I-68 at Keysers Ridge and hit the road.

It’s not the easiest route to follow. The National Road is designated as US 40 where it enters Maryland, but then it changes to Alt 40 at Keysers Ridge. It stays that way to Cumberland, beyond which the route changes designations several times. In various places it is US 40, Alt 40, Scenic 40, Route 144, and even I-68. Occasionally, it’s even called the National Road.

It’s not the easiest route to follow. The National Road is designated as US 40 where it enters Maryland, but then it changes to Alt 40 at Keysers Ridge. It stays that way to Cumberland, beyond which the route changes designations several times. In various places it is US 40, Alt 40, Scenic 40, Route 144, and even I-68. Occasionally, it’s even called the National Road.

First Stop: Grantsville

I originally had planned to stay overnight in Grantsville on my way home from Morgantown and explore the state parks and forests of far western Maryland. But after two days in West Virginia, I felt I’d seen enough tree-covered mountains and decided to head home early. But I did want to check out the Casselman Inn in Grantsville where I had planned to stay.

I pulled into Grantsville after a relaxing, traffic-free drive along the National Road from Keysers Ridge and stopped at the inn.

The hotel now called the Casselman Inn dates back to 1842. It was one of many inns along the busy road that served travelers arriving by stagecoach, covered wagon, horse, and foot. It is one of only a few such inns along the National Road that still survive. You can stay in a room in the historic inn, or in the two-story motel unit that has been added behind it. The inn has a restaurant and bakery, so I decided to have breakfast there before moving on.

- The hotel circa 1915.

- The Casselman Inn today.

The white cast iron mile marker in front of the inn is one of the original markers installed in 1835 by the state of Maryland when it assumed control of the road. One side shows the number of miles to the western end of the National Road (“106 to Wheeling”) and to the next town in that direction (“to Petersburgh 12,” now Addison, Pennsylvania). The other side shows the mileage to Cumberland, the eastern end of the road, and Frostburg, the next town in that direction.

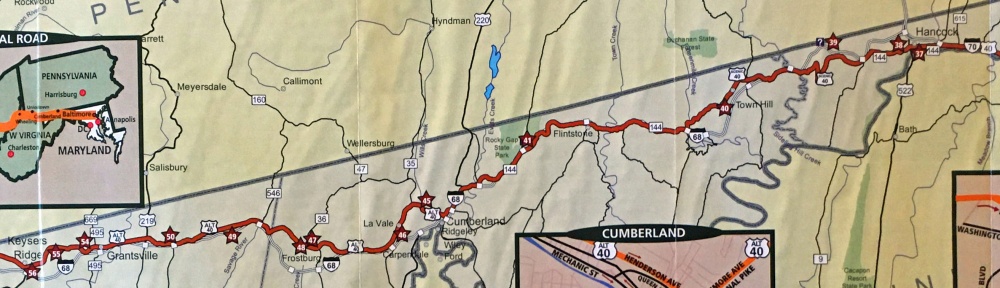

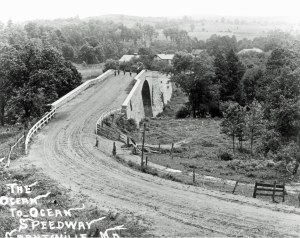

Just down the road in a small park is one of the historical highlights of the route, the Casselman River Bridge. Begun in 1813, it was at the time the largest single-span stone arch bridge in the country. It was in continual use as a highway bridge until 1933, when a new bridge opened nearby. If you walk over the bridge, you’ll see the year 1911 carved in stone, marking the year the bridge underwent a major restoration and strengthening for motorized traffic.

- The Casselman River Bridge circa 1910. The National Road never spanned “Ocean to Ocean.”

- At 354 feet long, with a roadway 48 feet wide, a span of 80 feet, and a 30-foot arch, it remains an impressive bridge.

The bridge’s arch was made high and wide enough to accommodate canal boats. The C&O Canal was originally planned to extend along the general route of the National Road to the Ohio River, but construction ended in Cumberland.

On the far side of the bridge is Spruce Forest Artisan Village, a cluster of historic structures where artisans work in various media and sell their artworks, and a café and a restaurant.

Frostburg and La Vale

The Gunter Hotel in Frostburg opened in 1897. Now housing both hotel rooms and apartments, it has been restored to its historic elegance.

Leaving Grantsville, I headed toward the city of Frostburg. The Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) rail trail passes right by here before veering north into Pennsylvania. Frostburg is also the terminus of the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad, which offers train rides between Cumberland and Frostburg. Sue and I stayed with friends in Frostburg a few years ago at the historic Gunter Hotel, using it as a base of operations for exploring the GAP trail.

Across the street from the hotel is the Princess Restaurant, a venerable diner where President Harry Truman and his wife Bess stopped to eat during a driving trip from their Missouri home back to Washington, D.C., in 1953.

Although the federal government financed and built the National Road, political controversy soon arose over who should pay to maintain it. The issue was resolved by transferring ownership of the road to the individual states it ran through. Once Maryland assumed control of its section, the state began building toll houses along it.

The first toll house on the National Road was built in the town of La Vale, just west of Cumberland, the road’s original eastern terminus. Constructed in 1834–35, the La Vale Toll House still stands by the roadside. The toll collector lived right inside the two-story, seven-sided building. Users of the road were charged a standard set of fares, depending on relatively how much wear and tear different vehicles or animals were likely to cause to the road. Signs on the outside of the toll house detail the rates.

Lost in Cumberland

I drove on to Cumberland, the largest city in western Maryland, the terminus of the C&O Canal, which extends to Washington, D.C., and the starting point for the GAP rail trail, which extends to Pittsburgh. But I didn’t stop to visit Cumberland. I was here to follow the National Road, and it skirts past downtown and twists and turns through the north side of the city.

Here, the going started to get tricky. I missed a turn trying to follow Alt 40 along Baltimore Avenue, but quickly realized my mistake and got back on track. I headed under I-68 and kept going on what I thought was the right road. It took me through a traffic circle and then another, and I started to feel like I’d lost the route again. Down the road a bit, I pulled into a parking lot to check my maps.

Neither my brochure map nor my AAA map provided enough detail, so I called up Google Maps. Alt 40 had somehow turned into Route 639. I knew that wasn’t the right way. I figured the National Road probably merged onto I-68 (also designated US 40) a couple of miles back. So I retraced my route and got on the interstate. My brochure map seemed to show that the National Road picked up again as Route 144, which soon began to parallel the interstate, but I missed the exit to it. So I stayed on I-68 until Flintstone and finally got on Route 144 there.

Over the Hills

The National Road in western Maryland traverses a series of parallel ridges and valleys trending roughly north-south, like waves washing toward the flat coastal plain. For much of the drive, you don’t really notice the true nature of this geography. The road just goes up and down, cutting through many of the lower ridges by following the courses of rivers and streams.

But as you approach Hancock, the National Road goes up and over a couple of high ridges. At the top of the first ridge, I pulled over into a parking area with a sweeping view. A wayside exhibit here informed me that this was Town Hill Overlook, dubbed the “Beauty Spot of Maryland” by auto tourists in the 1920s.

It is quite a view, said to encompass three states, presumably Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. To the east you can clearly see the long ridge of equally high Sideling Hill, as well as the deep notch in it that I-68 passes through. When the interstate was built through here, the steep grade of the National Road over Sideling Hill made engineers decide to blast through the mountain rather than follow the old road. The resulting roadcut is now something of a tourist attraction. There is a Maryland visitor center on I-68 on the eastern side of Sideling Hill where you can view the exposed rock layers.

Hotels were built on many of the mountain summits along the National Road. Across the road from Town Hill Overlook stands one of the earliest. The Town Hill Hotel began as a fruit stand in 1916, became a hotel and restaurant by 1920, and is now a bed and breakfast. The hotel offers shuttle service for bicyclists traveling along the C&O Canal from Little Orleans (Mile 140.9), about 8 very hilly miles away.

Hancock and the End of the Road

After descending Town Hill, I followed a Scenic 40 sign and was shunted back onto I-68 for a short distance. Later reviewing my route on Google Maps, it seemed I could have stayed on McFarland Road and skipped the interstate. Then I made the long and steep traverse up, over, and down Sideling Hill. It made me appreciate why highway planners routed the interstate through and not over the mountain.

The toll house near Hancock. One would have to be extra careful when stepping out of the front door.

My National Road brochure alerted me to a historic site I hadn’t known about, another toll house just outside of Hancock. Built around 1922, this one looks quite different from the toll house in La Vale. While this too served as both tollgate and toll keeper’s residence, it looks like a cozy little brick house, although one set rather close to the road. The toll rate signs on its walls show the same rates as La Vale.

I was now nearing the end of my drive on the National Road. I stopped in Hancock for a short bicycle ride along the C&O Canal towpath and then headed for my last stop.

The Blue Goose Market is at the far eastern end of Hancock, just before the National Road (here Route 144) merges onto I-70. A combination gift shop, gourmet market, and bakery, it has become a traditional stop for me and Sue when we visit Hancock to bike along the C&O Canal or on the Western Maryland Rail Trail. It has a great selection of freshly baked pies, many available by the slice. I chose a slice of crumb-topped Dutch apple pie and ate it on a picnic table outside. I also picked up a butter rum cake, a favorite of ours, to bring home.

The Blue Goose Market is at the far eastern end of Hancock, just before the National Road (here Route 144) merges onto I-70. A combination gift shop, gourmet market, and bakery, it has become a traditional stop for me and Sue when we visit Hancock to bike along the C&O Canal or on the Western Maryland Rail Trail. It has a great selection of freshly baked pies, many available by the slice. I chose a slice of crumb-topped Dutch apple pie and ate it on a picnic table outside. I also picked up a butter rum cake, a favorite of ours, to bring home.

I had spent the entire morning traveling about 70 miles. The 90 miles from Hancock to home would take an hour and a half. Travel by interstate highway has its place, but the National Road takes you through towns and countryside, not just past them, and rewards you with some roadside history along the way.

I highly recommend the drive. Just be sure to bring maps.

Historical photos: Maryland State Archives, Robert G. Merrick Archives of Maryland Historical Photographs.

More images and information: The National Road in Maryland (2019), by Robert P. Savitt, one of those “Images of America” books with sepia-toned covers, has dozens of historical photographs of the National Road from across Maryland, along with some concise historical background.

David Romanowski, 2021

Pingback: “Bike Walk Drive” at 100 | Bike Walk Drive